Abstract

The hypothesis in this essay is to consider the body as Image Queen in the history of art. The concept of “Image Queen” is proposed by Jacques-Alain Miller as an element of the imaginary register of language experience which equates it with the master signifier in the register of the symbolic.

The power of symbols in culture and in the minds of men and women is not rooted only in its duality and in its capacity to express the inexpressible; its performativity or its “symbolic efficacy” lies, above all, in the possibility of presenting that which is contingent or imaginary as obvious, necessary, and unavoidable.

That competence to present as natural that which is, at least partially, imaginary is a particular evidence of the body. This is so much so that nobody doubts its “biological” nature, its very existence, and the experience of the body is far from the different operations which society or culture have performed—and still perform—on that body. In the style of what Marcel Mauss thought of as “techniques of the body” in the 1930s, a concept which would be taken up by Michel Foucault (1975 [1991]) and his idea of the body as the meeting place for power relations and knowledge. That is where the vision of the industrial revolution and capitalism building a body specifically made for the machine and for discipline—also demanded by the national state in the battlefields—originates.

After these general considerations, in this essay we will present different fragmentary situations in the history of art, articulating their methods and approaches with those of Lacanian psychoanalysis. The conjuncture will be provided by the concept “Image Queen”, in the sense that is given to this expression by Jacques-Alain Miller (1995 [1998]), when he proposes this syntagma as that element of the imaginary register which could be equated with the “master signifier” in the symbolic register.

Although signifiers are not characterized by occupying a privileged place—we rather speak of equality of the signifiers which are defined by opposition and which are susceptible of metaphor and metonymy—it is by an analytical operation that a signifier is characterized as master, unsuccessfully representing the subject. The subject is an effect of the movement of the chain; it is not an individual, a person, but a subject of the unconscious that is represented by a signifier, for another signifier. If the master signifier is the main element of the symbolic register, the Image Queen will be the main element of the imaginary register.

The expression has its difficulties, as Miller explains, because the same movement of proposing it as an element of the imaginary requires its significantization. In psychoanalysis, an image reigns when it acquires a symbolic status. The same could be said in general of those objects or situations to which the history of art has directed its attention. However, while it is obvious that images abound in the history of art, the Image Queen has its own characteristics which make it different from the signifier, the main one being that it does not represent the subject.

The Image Queen is coordinated with jouissance. It is that in which the imaginary is tied to jouissance. This is what can be read as an example in Freud’s text (1936 [2008]) Letter to Romain Rolland (A Disturbance of Memory on the Acropolis) where he relates an effect of subjective division experienced by himself when he arrived and saw the Acropolis for the first time: he says that there was in him a person who knew that the Acropolis really existed and, at the same time, another person who seemed to doubt it.

In psychoanalysis, the images that dominate can be enumerated, and Miller (1995 [1998]) summarizes them in three in Elucidation of Lacan: 1. one’s own body, 2. the body of the Other, and 3. the phallus. We suggest reading this text to delve into the concept of the Image Queen.

This essay aims to take Miller’s hypothesis to the field of art history, as a game, as a bet, but as a serious matter, to address some Image Queens in art over the centuries.

In his text, Miller begins this game and ventures that the prevailing image in Greek antiquity is the face. The Greek word for face is prosopon and it designates that which we present to the eye, more precisely “in front of the face or mask.” In Latin it is the origin of the term “person.” Prosopon, then, is in opposition to the rest of the body, which is always more or less dressed, not given to the naked eye.

It was the face in ancient Greece, but what are the Image Queens which tied a jouissance in the subjectivities of other eras? We will try to give some answers in the following sections.

Jouissance in the Eternal Present: Hunting

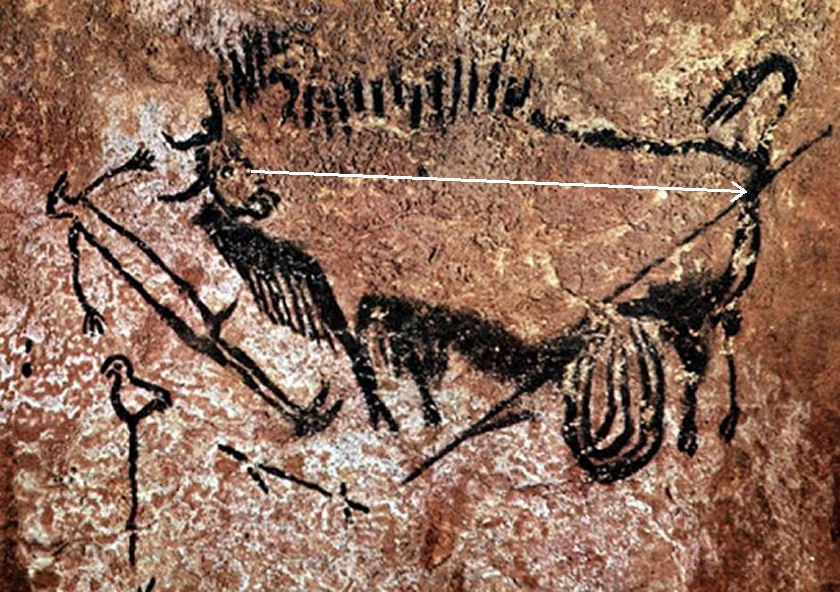

The first bodily representations come from prehistoric caves, almost always coexisting with those of animals. It can be said that the body of the latter, much more powerful than the human, is the Image Queen in that timeless period.

When the artist and magician paints the animal, he does it in a formidable scale and with a realism in the representation of movement which was admired by European artists since the late nineteenth century. That does not happen with the human body in the same period, when its representation is simple and schematic.

Art is mixed here—as on many other occasions—with magic and the supernatural. Animals, on which they depended for their sustenance and clothing, is identified with the power of nature and, therefore, with the divine and the inexplicable (Giedon, 1981 [1985]). Capturing the image is hunting the animal and also appropriating its vital energy. This is attested to by the arrows painted on their bodies; many times, there are hints of real tips which pierce the image of the beast that has been wounded to death. His superiority places the hunter in a situation of veneration and admiration for his object of desire, which apparently contradicts his intention to kill it. However, it is in fact a ritual sacrifice related to spirits, diffuse at first, which would be later crystallized symbolically in the zoomorphic deities of the first civilizations such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, or America. After the death of the animal, the process of its (in)corporation begins, through its flesh and the skin that covers its body. We also know Freud’s myth about the primal horde and the totem feast: it is thanks to the incorporation of the meat of the dead totem animal that its qualities are acquired; in other words, it is thanks to the identification with the symbol which kills the thing that its significant and imaginary properties are introjected.

Let’s take as an example the so-called “Hunting Scene” in the cave of Lascaux (France). What predominates is the enormous body of the injured animal, which at the same time writhes in pain and attacks its victimizer. Its head turns desperately toward the open wound in its abdomen, through which its viscera hang. However, it will crush the hunter, who is falling in the represented scene. His body is reduced to a few lines. His head has been replaced by that of a bird, perhaps a totem sign, an assumption reinforced by a cane which, whether contemporary with the scene or not, is a fact impossible to verify with precision; it is also an integral part of the scene or, in other words, it forms part of its history and meaning. The cane handle is also a bird. The Image Queen of the animal provides him with life and death, jouissance and pain. But also a symbolic notion of the body which places it in a situation of inferiority while allowing it to resolve the apparent opposition between the erotic and the thanatotic, since the image of the hunter is ithyphallic. Even the hunter’s phallus points to the animal, as if pointing out where the phallic value can be found.

In this case, the Image Queen privileges the body… of the Other. Who else than nature, represented by the great animals, the immensity of the sky and the Earth, of the vegetation in its vast territories, could have occupied the place of the Other for the prehistoric caveperson? The body of the animal Other is that which is represented in Lascaux, in great detail and in superiority to that of the human body. An indomitable Other that, in that final moment of being hunted, that instant when its domination is achieved, also crushes the hunter.

En este caso, la imagen reina privilegia el cuerpo… del Otro. ¿Quién más que la naturaleza, representada por los grandes animales, la inmensidad del cielo y de la tierra, de la vegetación en sus amplísimos territorios, habrá ocupado el lugar del Otro para el cavernícola prehistórico? El cuerpo del Otro animal es el que se representa en Lascaux, con sumo detalle y en superioridad a la del cuerpo humano. Un Otro indomeñable que, en ese momento final de ser cazado, ese instante en el que se logra su dominación, aplasta también al cazador.

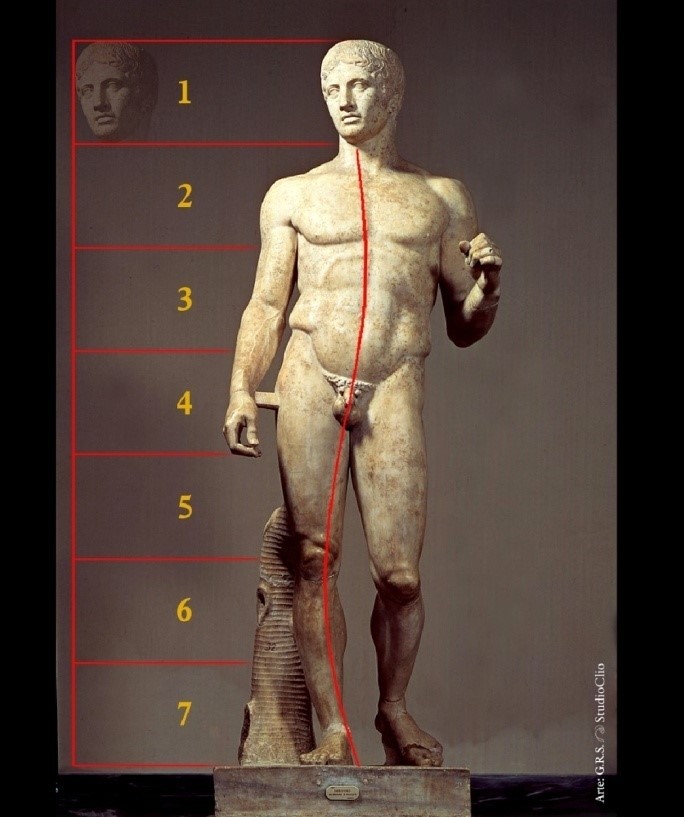

The Naked Man, a Perfect Measure of Desire: The Apollonian Canon

In classical times, the Image Queen of the body is an idea articulated with beauty lacking in materiality, since it is based on a god; Apollo and human perceptual mechanisms are not capable of contemplating it. Plato, although he recognized in eroticism a way to get to truth, distrusted the ability of the senses to grasp the reality of things, among them, their beauty, so linked to both Eros—and, therefore, to the body—and his mother, Aphrodite. And the idea of beauty lay in the male nude, which was not often pointed out from a gender perspective, since the canon, as we said, was based on Apollo, god of supreme beauty (Clark, 1956 [1996]). When Polykleitos applied the rules of the system he had created in “The Canon”—now lost—to sculpture, he gave symbolic expression to the body of the male citizen (not the female citizen) independent but subordinate to the polis. Respecting the relationship of the parts with the whole or guiding idea, but without their losing their independence, is the founding principle of this poetics or organization of forms. This was articulated with a policy, or an order of forces in Athenian democracy, the obedience of all citizens to the polis, as interchangeable units, but without their losing their individuality. He manages to put into action the Apollonian Image Queen with the revolutionary invention of the contrapposto, a pose where Egyptian or Mesopotamian hieratic attitude is altered—societies based on permanence and not on change, unlike the classic, which is presented as a discontinuity—reaching the formal solution to a problem which can be found in the pre-Socratic philosophers of the sixth century B.C.: the relationship between stillness and movement, between that which remains and that which changes. This “vitality” and closeness to Apollo clearly lay in ephebes and not in women, since contrary to what one might think, the nude of the so-called “beautiful sex” appeared much later. This homoerotic canon has survived surreptitiously in the West, even in Christianity, as for example in the figure of Saint Sebastian. It was resurrected from antiquity and put back into force after the discovery of the “Apollo Belvedere” near the sea. The latter is a Hellenistic sculpture that was consecrated as the ideal of beauty in the eighteenth century by Winckelmann, the first thinker who applied scientific rules—mainly based on archeology—to the study of art history. It is no coincidence that this devotee of Greece was homosexual; neither is it that this fact has been generally overlooked by art history. However, the weight that his ideas had in the “cultured” West, his consecration of the ephebic body adjusted to Apollonian rules: a priori formal principles which might make it possible to explain its beauty and impact on the senses, as well as its possible resonance in the absolute idea of beauty. However, it is important to remember that Plato distrusted, above all, the most beautiful objects, since their unreal beauty distanced men from the contemplation of true perfection, which was obviously ideal.

The phallic logic, from psychoanalysis, is thought as that which privileges measure, symmetry, order, the rational and the countable. It is no coincidence that the epoch when the canon of beauty was male—through the idea of supreme beauty of the god Apollo—was governed by parameters linked to the measurable as a technique to achieve the perfect representation of the body. The Image Queen in this period is then the male human body, founded on Apollo’s unrepresentable beauty.

Enlightened Venus

Venus—Aphrodite to the Greeks—was, as we know, the goddess of love in its carnal form. Always accompanied by Eros, she is also distinguished by other attributes, such as roses and a white dove. François Boucher (1703-1790), the favorite painter of the Marquise de Pompadour, who was an influential and enlightened lover of Louis XV, painted several portraits of her. The one we now present, “La toilette de Venus,” was painted in 1751 and can be clearly contrasted with another where she is portrayed in a wide skirt on which a book rests. Although the female reader is a Rococo genre related to the publishing boom and to what Chartier characterizes as an urban use of the printed image, it is remarkable that Jeanne, sponsor of the Encyclopedia, appears accompanied by a book. It is also notable that, in other representations such as this one, she appears personifying Venus, who is not related to the intellect (Boyme, 1987 [1994]). In addition to obvious contrasts related to issues of male domination, possession, and voyeurism—monarchical in this case—, it is worth noting, however, that both representations of Madame de Pompadour coincide at a certain point with the project of the Enlightenment, since erotic education was not absent from the program, as the Marquis de Sade’s work shows us, for example. It was an extraordinarily frank and bold century in its erotic practices and representations. That is why it can be thought that this allegory brings to the scene a promise of carnal jouissance intimately linked to luxury. The luxurious female body is the Image Queen and Boucher shows us an opulent image of the king’s mistress, who appears surrounded by all imaginable riches and luxuries, willing, like France, to satisfy the absolute monarch’s wishes, whose body, as Foucault points out, was equivalent to that of the State.

It is not a minor fact for psychoanalysis that the canon of beauty began as that of a masculine ideal and that it later moved toward the “beautiful sex.” There is both an artistic inclination toward the female body in the representation of beauty as the favorite and a shift in the gaze toward the male body. Just as the questioning of the Name of the Father has led different logics grouped in the so-called “feminization of the world” to become relevant (Miller & Laurent [2005]), the Image Queen of the male body shifts toward the female nude and opulence. From Apollo to Venus, elements of the divine now appear, as well as mundane products which do not respond to an orderly disposition, but which are intermingled, fallen, disordered, in promiscuity with deities, animals, things. Even in what appears to be the interior, one can also find an exterior by paying attention to the background of the image; there is a confusion between what is inside and outside. Order is questioned.

Venus Supplanted by the Vagina

The nineteenth century, marked by the Industrial Revolution, nationalism, and colonialism, was extremely important in the consecration of the modern way of life. A century that witnessed opposing movements in its poetic/political motivations such as Neoclassicism, Romanticism, Realism, Impressionism, and Symbolism was also cut across by different conflicting political and scientific conceptions, mainly liberalism, socialism, and positivism.

In the junction of the latter, apparently so far apart from one other, lies Realism, a movement that was led in France by Gustave Courbet (1819-1877). Almost all art historians are familiar with one of his quotes, which sums up his artistic and political commitment: “Show me an angel and I will paint one.” For Courbet, a forerunner of the avant-garde, art should be at the service of reality and not submitted to any canon. This adherence to truth in art led him to explore themes which had been absent from his career, such as the lives of peasants and those who were marginalized from nineteenth-century progress (1973 [1981]). He did so with a fidelity that owes much to technological advances, as one might wonder whether he could have developed—as Degas did, for example— without the invention of photography.

The Image Queen in Courbet’s work is life itself, without bourgeois humanist idealizations. His best-known painting, “A Burial at Ornans,” is often compared in this sense with El Greco’s “The Burial of the Count of Orgaz” (1588). Courbet offers a stark look of death. The center and the foreground of the scene are occupied by an open grave in a rural burial. A dog snoops nearby, downplaying the importance of the ceremony that is taking place under a leaden sky. To the left and right of the crudely dug hole in the ground are the clergy and the peasants. The composition is markedly horizontal, as if to highlight the impossibility of an “ascent.” In contrast, two and a half centuries earlier, the work of El Greco (1541-1614) was markedly vertical, where the soul of the deceased was detached from his body and ascended to heaven—certainly to that of the just.

“The Origin of the World,” painted by Courbet in 1866, shows us a truncated image of a female body lying with the genitals exposed in the foreground. The crudeness of the image—especially considering the time when it was painted— can be thought of in the general context of the eminently anti-romantic proposal of Realism.

It is remarkable that with the passage from the representation of the male body as a canon of beauty to that of the female body, Courbet’s blunt questioning of the idea of canon produced a work showing, in the foreground, what had remained outside the gaze in the “beautiful female body”: the vagina.

It is well known that Lacan had to cover this work, acquired for his country house, with a double-bottomed frame system which allowed it to be hidden or shown, as it made visitors very uneasy.

The female body was the Image Queen, but on condition that her female genitals be kept veiled. That horror caused by the exposed vagina is an indication that the image might moor jouissance. It is an image which does not show bodily completeness, which is not oriented by the beauty of the female body. On the contrary, it strips the representation of the harmony which ensures contemplation and strikes a blow to the gaze. There is no ostentation or divinity; it removes adjectives from the body to simply show a vagina, a pair of thighs, a breast, and a navel flung on some seemingly white sheets. We cannot even see whether it is a dead or a living body.

As we said about “A Burial at Ornans,” Courbet removes the transcendence that a funeral ritual can have in order to show death without a Paradise, without an ascent. There is a step which separates the verticality of the divine from the horizontality of the earthly. From the female body as an idealized whole to the pornographic fragment.

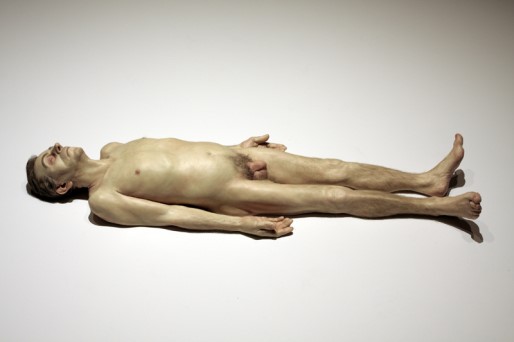

From Plausibility to Hyperrealism: The Triumph of Science

Ron Mueck (1958), an Australian sculptor, is known for the striking verisimilitude of his human and animal figures, stylistically and conceptually related to the Hyperrealism of the 1970s. Using scientific and technological resources, he achieves an extreme naturalism in his sculptures, which are always gigantic or tiny, bigger or smaller in comparison with the original model. None of his figures respect the real size of the human or animal body, although they do achieve a verisimilitude which produces a certain ominous feeling in the viewer.

Having worked for the film industry, Mueck does not choose to create supernatural or science fiction figures, despite the unlimited availability of special effects today. His sculptures allow the viewer’s eye to meddle in the almost microscopic details of the body, thanks to the instrumental use of scientific technology. The daily poses of his figures, thanks to which his work has become part of costumbrismo, do not express anything extraordinary, but rather turn the ordinary and frequent into something of extreme interest to the viewer. More or less like the gesture of Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) who, by choosing an indifferent and ordinary industrial product for everyone, transforms it into a ready-made product worthy of exhibition.

His works show a moment of stoppage which does not refer to a clear past or future in the situations they represent, but they do show a gesture which occupies a time lapse. They are like three-dimensional photos taken in the middle of a minimal story which has begun and continues. Like a stopped film, they tell only what they show. In fact, there is no context enriching the story of the figure; there may be an object, a light put in some kind of perspective at best. Perhaps this is what makes them suggestive, disturbing, and attractive, in addition to—naturally—their hyperrealism.

The figure we have chosen to present here is “Dead Dad” (1996). It is a sculpture which uses the body of his own father as a model. He even used the original hair for the figure. This work is paradigmatic of Mueck’s work. In addition to the obvious connection which can be made with the great philosophical and psychoanalytic theme of the dead Father, there are other reasons: one of them is that he used the image of his dead father to make the sculpture. The reuse of human corpse fragments is a unique feature of our times, made possible by science and the mandate to recycle. In addition, this is another one of his works which focuses on a body that is old and shaped by time and life. But this time it has been struck by death. His sculptures are known to have been branded as looking alive; this one only needs to be actually dead. “Dead Dad” does not represent the death of Christ or that of some saint or monarch, like so many horizontal sculptures that can be found in many temples. It is not about the death of God; there is no transcendence in this death; it is that of an ordinary citizen. Is death the impossible challenge for science?

We said that one effect of his work is that his sculptures seem to be alive, but there is another side effect that unsettles the viewer: it is the question of what a body really is; is it an image, is it the organs and bones, is it a shell, is it something living, is it an object? Mueck’s bodies, in spite of being empty shells inside, exert a mirror fascination which does not appease, but rather leads to one’s being reflected—reflecting on oneself—in that Image Queen.

Throughout the selection of works that we have looked at, the Image Queen has acquired predominance over different bodies according to the period.

From the body of the animal as a privileged Other to the right phallic measure of the homoerotic body. Later on, from the voluptuous representation of the female body becoming the favorite to the bodily realism stripped of the beautiful ideal. Thus, we arrive at an art that puts the viewer’s body in a state of questioning. The body proves to be an Image Queen in whatever format it is presented, always carrying that fascination which comes with its contemplation.

The art which we have seen here shows us a path indicating the attempt to represent otherness—animality, divinity, femininity, even death—the body being the support with which we try to capture it, to point it out as the Other of each epoch in a gesture aspiring to bring it to unity, to identity, opposite to otherness.

But there is something else: this Image Queen that produces fascination, fear, contemplation, rejection, or admiration; this Image Queen that is the body becomes an object stripped of its attributes of beauty and vitality in “Dead Dad.” This work seems to be shouting: After all, there’s only waste left! But the image reigns.